For over 150 years five Mughal emperors had ruled much of northern India with relative success. Following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the empire entered a period of such instability, that 10 emperors sat on the throne in the next 50 years. Fratricidal civil wars, foreign invasions, and court intrigues led to the decline of what was then amongst the world’s largest and richest Empires. The 1739 invasion of Nadir Shah dealt a final blow to whatever prestige that the Mughals retained after which there started a mad scramble among the many opportunistic powers to take advantage of the chaos that followed.

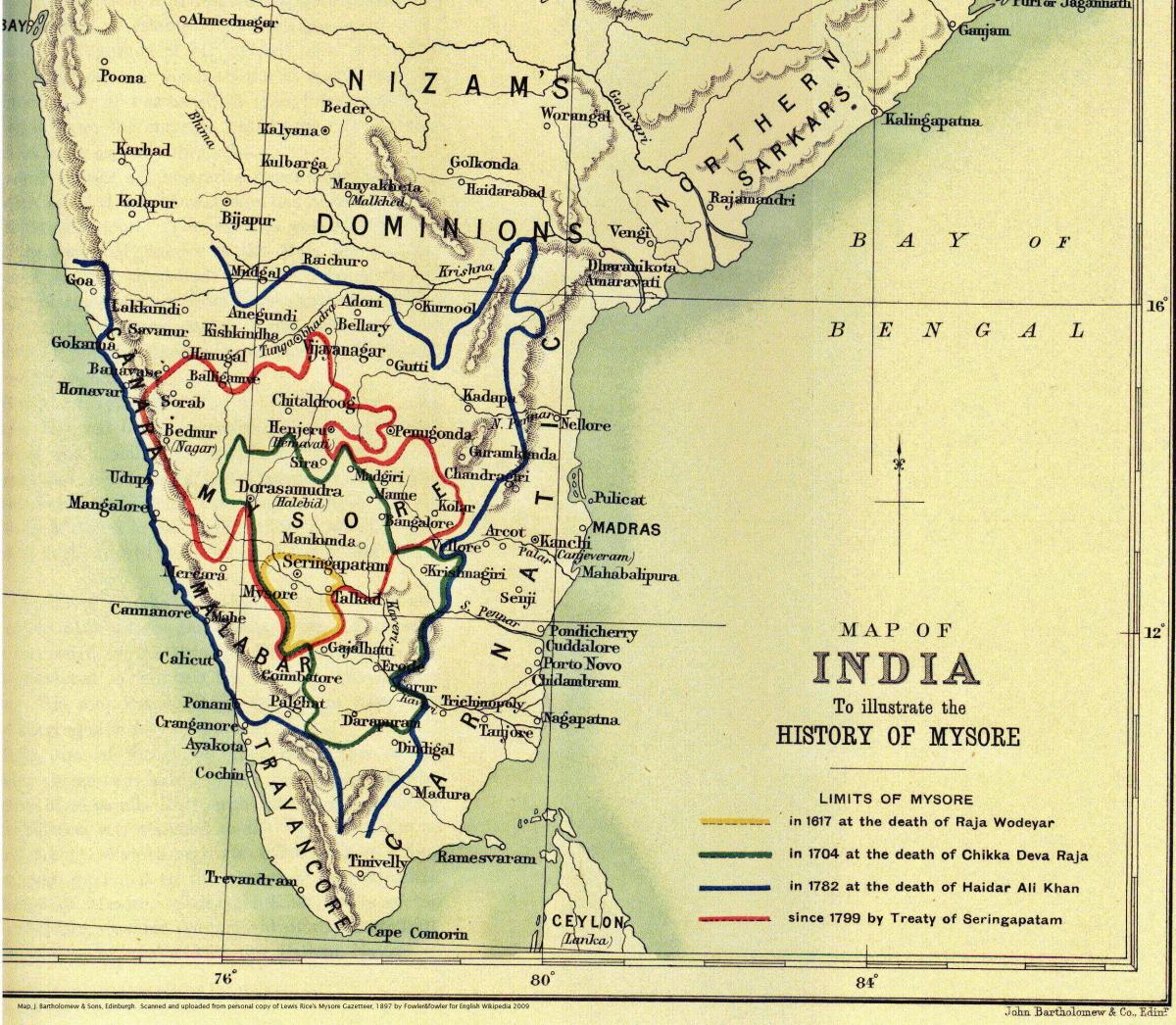

The East India Company, having defeated the Mughal army in the battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), joined the land-grabbing enterprise. Similarly, the Marathas, led by ambitious generals like Peshwa Bajirao I (d.1740) also started to expand at the cost of the Mughal empire. The Sikhs in the Punjab and the Nizam in the Deccan also declared independence from Mughal rule. The decline of the Mughals and the resultant political strife gave rise to many foreign as well as local powers contending to ‘invest heavily in military innovation as well as professional soldiers’. Haidar Ali was one such professional soldier and military adventurer who rose through the ranks in the army of Mysore and helped carve an empire for his employer, the Wodeyar raja of Mysore. He later usurped power from the raja after relegating him to a titular head to become the nawab himself. It was but natural for him to come into conflict with other regional land-grabbing powers in order to protect his recently acquired domain. This made him to modernize the military along European lines. From using new technologies on the battlefield to ‘constituting a department of Brahmin revenue clerks’ who were adept at garnering revenue from all parts of Mysore’s ever-expanding territory, his statesmanship propelled Mysore to become one of South India’s strongest powers, stretching from Dharwar in the north to Dindigul in the south and from the Arabian sea in the west to the Ghats which rose from the Carnatic in the east.

The first Anglo-Mysore war which was the first time that an Indian power dictated terms to the British at the gates of Madras saw the18 year old Tipu Sultan aiding his father Haidar Ali by staying guard with part of the army at Bangalore to stop any British move to outflank Haidar Ali. The 2nd Anglo Mysore war saw a most humiliating British defeat at Pollilur where for the first and only time in Indian history a European army was decimated by an Indian one with Tipu himself among the commanders leading the charge into the British column led by Lt. Col. Baillie who would with many Englishmen be made prisoner of Mysore that day. It was in midst of this war while both father and son were campaigning at different ends of Mysore that Haidar Ali passed away in 1782 and Tipu Sultan succeeded his father to the throne of Mysore. Unlike his father, who had risen from humble beginnings and was illiterate, Tipu Sultan had received the education of a prince, which was immersed in the Indo-Persian culture of the time. Alongside his studies of Persian, Arabic, Hindustani, and Kannada, he was well versed in Islamic thought as well as horsemanship, archery, and the military arts that he learned from the teachers appointed by his father and through years of experience participating in military campaigns at his father’s side.

Tipu Sultan was one of the most creative, innovative, and capable rulers of the pre-colonial period in India. His innovations in areas as varied as agriculture, irrigation, as well as social reforms were unparalleled for Indian rulers of that time. Tactically, the Mysorean army was as advanced as the military of the East India Company. Tipu also excelled in taking the best of European military methods and combining them with the best of Mysorean military traditions. This steady rise of Mysore as a power that continuously confronted the British in its march towards dominance of Southern India and it’s friendship with Revolutionary France did not pass the notice of the highest echelons of the British government in London who now began to actively assist the East India Company to quell this Indian monarch whose freethinking and creative mind was very different from the minds of contemporary Indian rulers around him.

In 1792 Mysore resolutely faced a coalition of the English, Nizam and the Marathas. In several pitched battles at locations spread across South India today, the Mysoreans matched the allies cannon volley by volley and even forced Lord Cornwallis’ and his army’s withdrawal from the walls of Seringapatam towards the start of 1792. However the arrival of the Maratha allies of the English meant that Tipu finally had to accept the British terms of surrender which involved paying a large indemnity to the British and giving up half of Mysore’s territory with handing over two of his sons’ as hostages till Mysore could fulfill these demands. The next few years saw Tipu Sultan striving to bring Mysore back to the path of recovery from the severe economic and material damage that it had suffered in the last war. While this was being done very successfully the English continued to scheme to bring down this one power that continued to stand as a bulwark against it in India. Finally the curtain would fall on this great drama on May 4, 1799 when Tipu Sultan fell fighting by his men’s’ side in the final hours of the 4th Anglo-Mysore war.

Tipu Sultan’s Mysore was an early example of a military fiscal state in India. This was a state, where a robust economy supported a strong army. Every arm of the state was geared to getting the best out of any revenue generating source be it trade, commerce, agriculture, manufacturing and taxation. It is no wonder that over nearly 30 years of continuous war with the English and its allies Mysore saw no famine or want and no rebellion induced by these factors; this was in no less measure on account of a strong reserve of wealth that the state built up for times of crisis. And it is this wealth that went towards creating some of the finest artifacts that Indo-Islamic civilization has ever produced and which are dispersed across the world today.

The Great loot of Seringapatam began in the evening of May 4, 1799 after his death and the total defeat of his army. Tipu’s palace, his treasury and the houses of the people of the city were plundered for 2 continuous days before some semblance of order could be maintained. Col. Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, in a letter dated 8 May, 1799 writes: “…Scarcely a house in the town was left un-plundered, and I understand that in the camp jewels of the greatest value, bars of gold, &c &c, have been offered for sale in the bazaars of the army by our soldiers, sepoys and followers…” He goes to write in another letter to his brother, Lord Mornington – “…priceless pearls were offered in exchange for a bottle of liquor….an army doctor was able to buy from a soldier two bracelets, set with diamonds. One among them was said to have been valued by a Hyderabad jeweller at BP 39000. The other bracelet was of such superlative value the jeweler could not fix a price for it…”

It was then suggested that a Prize Committee should be set up by Maj. Gen Harris, under the Chairmanship of General Floyd to determine the quantum of prize money to be distributed among the rank and file of the army and others. Each soldier would receive his share based on his rank. A systematic study of several recorded versions of the plunder, including the jewels looted and hidden away, estimates the value of the Prize money at BP360000. Apart from the magnificent gem studded, gold tiger throne and sparkling silver howdahs, there were gold and silver plates, expensive carpets, bales of fine muslin and silk as well as Tipu’s excellent library.

The throne of Tipu Sultan was in the form of a life size Tiger, clothed in shimmering gold metal sheets and studded with dazzling precious stones. The Asiatic Annual Register (1799) while providing the reasons and justifications for breaking up the throne during the sack of Seringapatam describes the features of the magnificent piece of art: ‘The Sultan’s throne being too unwieldy to be carried, had been broken up: it was a howdah upon a tyger, covered with sheet gold; the ascent to it was by silver steps, gilt, having silver nails and all other fastenings of the same metal. The canopy was alike superb, and decorated with a costly fringe of fine pearls all around it. The eyes and teeth of tyger were of glass. It was valued at 60,000 pagodas …‘

After the throne was dismantled, what remained was a massive Tiger head, two small tiger heads and the gorgeous bird of Paradise (Huma) that perched over the ornamental canopy of the royal seat. The tiger head was presented to King George III by Earl Mornington, Governor General of India in 1800. It now rests in the Royal Collection in the United Kingdom. The Huma bird on Tipu’s canopy, is a beautiful specimen of oriental jewellery. It appears in a fluttering posture and occupies the central part of the gold canopy of Tipu’s throne.This fabulous bird, made of solid gold, nearly the size of a pigeon and covered with precious stones, is six inches high and has a brilliant wingspan nearly eight inches wide. The neck is of emeralds and body of diamonds with three bands of rubies. The beak is a large emerald, tipped with gold and has another emerald suspended from it. The pendant hanging from it has a ruby and two pearls, and the crusting on the head are of emerald and pearl. It’s back is one large and beautiful carbuncle, the long tail resembles that of a peacock, and is studded with jewels. The body and the tail are copiously studded with rare gems so closely that the gold is hardly visible. It’s eyes are two brilliant carbuncles. The pearl ornamented breast is covered with diamonds. It’s wings, spread as though it is hovering, are lined with diamonds and other stones. This magnificent bird is also today in the collection of the King of England and forms part of the Royal Collection Trust.

There were 8 tiger head shaped finials at the eight corners of the throne. These finials had the main gold surface of the head worked decorated with fine dotted pointille punching; symmetrically set on either side of the centre line with foiled table-cut diamonds, foiled cabochon rubies and foiled cabochon emeralds of varying sizes, with larger rubies set on the eyes and the tongue, the teeth set with foiled table-cut diamonds. The ears projecting above the head decorated with chased lines and further pointille punching. Of these 8 finials the whereabouts of only 3 are clear with one in the Clive collection at Powis castle in Scotland and the other two being sold at Bonhams Auction house over the past 2 decades with the last one sold fetching a price of what will be in India Rupees 3 Crores. The current locations of the remaining finials are unknown.

Windsor Castle has Tipu’s turban ornament, the ‘sarpech’ as well as his war helmet. A part of another be-jewelled turban ornament in the form of a brooch from the family of Captain Cochrane who took part in the storming of Seringapatam, is at the V&A which is part of 3 valuable necklaces and 3 brooches made of the gems from the turban ornament of Tipu Sultan. The V&A Museum in London has an exquisite Emerald and Diamond Set as well as a Ruby and Diamond Set all in from of Bracelets, brooches, necklaces and pendants which were made of precious gems plundered from Tipu Sultan’s treasury. A lot titled ‘An Indian antique gold ring’ with it described as being a heavy oval ring with the name of the Hindu God Rama in raised Devenagri script surrounded by chased floral buds to the octagonal base and ornate shoulders and hoop, and weighing 41.2 grams was sold in 2019 for a princely sum of Rupees one and a half crores.

Tipu Sultan’s palace also yielded up another curious treasure. This was not made of gold or silver but of wood. The tiger, an almost life-sized wooden semi-automaton, mauls a European soldier lying on his back. Concealed inside the tiger’s body, behind a hinged flap, is an organ which can be operated by turning the handle next to it. This simultaneously makes the man’s arm lift up and down and produces noises intended to imitate his dying moans. This was presented to the East India Company and taken to London where it is today among the V&A’s most popular objects. Tipu identified himself and his army with the Tiger which was a feared and respected animal in Mysore and used it’s symbolism like the tiger stripe, which was called ‘bubri’ as his state insignia.

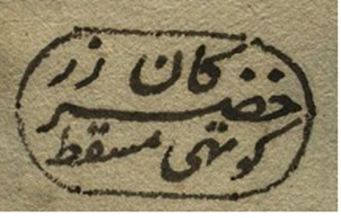

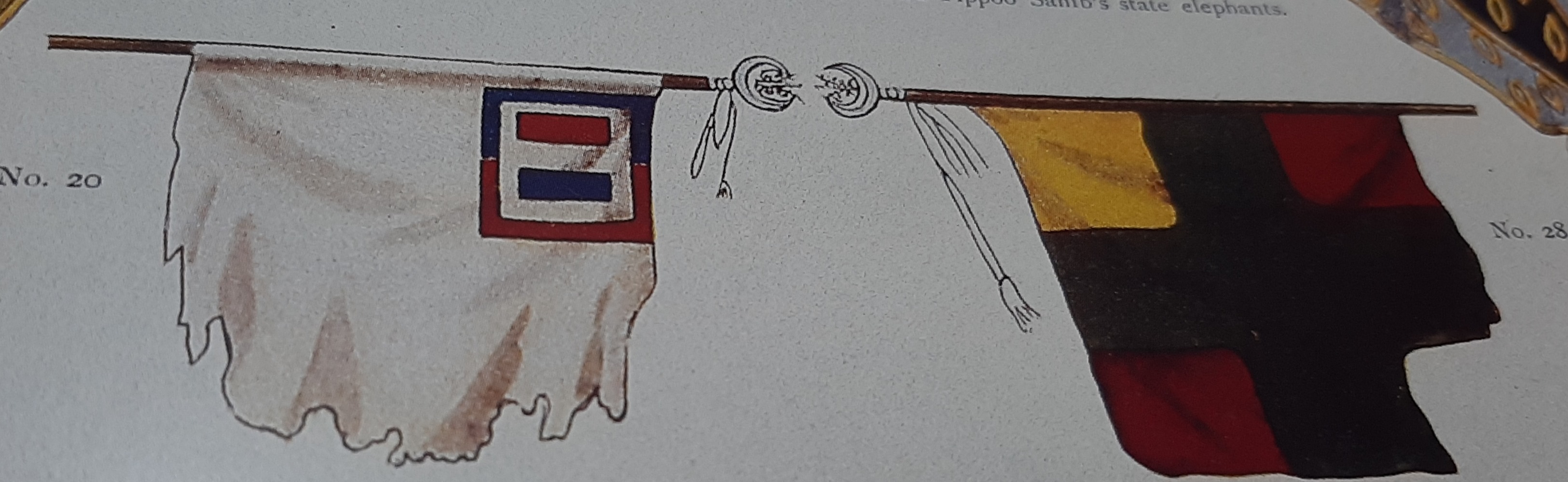

Later, Wellesley took charge of Tipu’s personal clothing, to prevent it from distributed as sacred relics to potential rebels. The Tower of London has Tipu’s quilted cap. The V&A has a dressing gown as well as a quilted helmet. The Royal Collection has his Horse Trapping and Horse’s Head Armour. Tipu’s Sun banner which was Mysore’s flag is now in the Windsor Collection and so is his magnificent private seal made of gold. The Royal Hospital Chelsea has staffs of four flags captured by the English in Seringapatam.

The capture of Seringapatam also led to several weapons from Mysore – magnificent swords, daggers, flintlocks and cannon being captured by the British. Most of the weaponry produced in Mysore during Tipu Sultan’s time reflected the aesthetic sense of Tipu’s personality carrying beautiful designs, gilt inscriptions in Arabic and Persian and tiger stripes or the tiger head displayed boldly on them. Many ornate swords are distributed across the V&A, Windsor Castle, Meyrick Collection and other private collections worldwide. A rare and fine Sword with bubri patterned watered blade from the Palace Armoury of Tipu Sultan in Seringapatam (circa 1782-99) with the brass hilt cast in one piece, the pommel consisting of a tiger’s head in the round, punched and engraved detail, bubri-patterns extending down the facetted grip, the quillons terminating in tiger-masks, one langet with bubri patterns and punched decoration, the other with a low-relief tiger-mask, the slender knuckle-guard terminating in a tiger-mask, the blade of curved sabre type, forged of watered steel formed into a repeating bubri pattern, later inlaid in gold on either side with the two-part inscription – ‘No Me Embaines Sin Honor/ No Me Saques Sin Razon’ which translates as ‘”Draw me not without reason, sheathe me not without honour” was in 2015 sold at auction in London for an astounding figure of what is Rupees Two crores and thirty lakhs in Indian currency.

Tipu Sultan’s firearms are today the pride of collections in Museums spread from London to Kuala Lumpur to Doha. The Powys collection and the Royal Collection, Windsor has very good examples of his firelocks as well as Brass cannon. The last time, which a Tipu firelock came up for auction in the West, was in 2019 where it sold for more than Rupees 60 lakhs. While these are the ‘sensational’ pieces looted from Seringapatam, the loot also extended to furniture – there are chairs with provenance to Tipu’s palace in the Oriental Club, London and the V&A. His ornate floral burhanpuri tent made of cotton, printed, painted and dyed is in the Powys Castle collection. A hookah of his was once in the possession of the noted antiquarian William Beekford. There are also caskets, medicine boxes and other ephemera from Seringapatam lying around in British army cantonments and clubs.

The court of Tipu Sultan was a reflection of Mysore’s prestige and prosperity. It was in fact an extension of Tipu Sultan’s unique personality and each of these objects associated with his court are testament to those four decades on India history, a mere blip in time yet one that was sufficient to ensure that the name of Mysore was heard across parliaments, public house and homes in London, Washington , Paris and Constantinople.